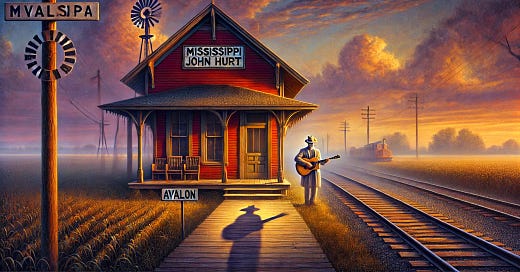

Mississippi John Hurt and the Fingers of Time

Exploring the gentle resonances of a timeless bluesman

Mississippi John Hurt’s music carries the burden of time — not as a weight, but as a thread weaving resilience, humanity and history into a sound that is intimate and weird, familiar and eternal.

Born on March 8, 1893, in Teoc, Mississippi, and raised in the small rural community of Avalon, Hurt’s life was steeped in the stillness of the Southern countryside. It was a world far from the explosive Delta blues of his contemporaries, and this remoteness shaped his sound. In Avalon’s isolation, Hurt found the space to craft his gentle but hard-driving sound. He didn’t meet the traveling bluesmen of the day. Instead, he learned his songs from older field hands in the county. Hurt’s fingerstyle guitar playing is not the insistent, raw cry of anguish of Charley Patton or Son House; instead, it is a gentle murmur, a soothing refrain that calls listeners to gather round and lean in.

Born during the Jim Crow era, Hurt grew up in a region marked by systemic racism and limited opportunities. Sharecropping and tenant farming were common, and these economic hardships often stifled the dreams of rural black communities. Yet amidst this adversity, Hurt’s community fostered a rich musical tradition, where gospel hymns, field hollers, and folk melodies intertwined to create a vibrant cultural tapestry. These influences became the foundation of Hurt’s unique sound. Amid these struggles, Hurt’s music emerges not as a lament but as a testament to the quiet resilience of his home, a good place in a harsh world.

Mississippi John Hurt’s journey into the world of recorded music began in 1927, when a talent scout from Okeh Records named Tommy Rockwell visited Carroll County to hear Willie Narmour, a local fiddle player who had recently won a competition. It was Narmour who introduced Hurt to Rockwell, leading to a trip to Memphis in 1928, where Hurt recorded eight sides for Okeh. Among these were the now-iconic tracks “Frankie” and “Nobody’s Dirty Business.”

Though only two songs from the session were initially released, the charm of Hurt’s refined fingerpicking style and guileless, soothing voice caught the attention of the label, which invited him to record additional sides in New York later that year. This second session produced legendary tracks like “Stack O’ Lee Blues,” “Louis Collins,” and “Spike Driver Blues,” the latter offering Hurt’s gentle, bittersweet take on the John Henry legend. Despite the quality and uniqueness of these recordings — so unlike the fiery intensity of Delta blues contemporaries — they sold poorly, dismissed as old-fashioned in a market leaning toward grittier, urban sounds. Coupled with the onset of the Great Depression, Hurt’s brief recording career came to an end, and he returned to Avalon, content to farm and play for friends, his remarkable talent left to linger far away from American ears.

Hurt’s rediscovery during the 1960s folk revival brought his artistry to a new audience. By then, he was a man in his seventies, yet his music retained its freshness and vitality, and time had only ennobled his voice. Albums like Rediscovered and The Immortal Mississippi John Hurt showcase the essence of his style: alternating bass lines that anchor his melodies, treble notes that sparkle with precision, and a voice as inviting and sweet as a fresh apple pie on a front porch swing.

The Poetry of His Fingers

“Avalon Blues,” written as an ode to his hometown, is a masterclass in Hurt’s fingerstyle technique. His thumb provides a steady, heartbeat-like pulse, dancing across the bass strings to establish a rhythmic foundation. Over this, his fingers pluck descending melodic lines that evoke both nostalgia and serenity. The effect is hypnotic: the melody floats above the rhythm, creating a sense of contrapuntal harmony.

Hurt’s playing is deceptively simple. Close listening reveals a mastery of dynamics, as soft pinches and subtle pull-offs breathe life into every note. In “Avalon Blues,” the rhythm is unhurried, the melody unadorned, yet the song conveys a deep sense of place and longing. His guitar lines do not merely accompany his lyrics; they converse with his words, harmonizing and filling the spaces between phrases with understated eloquence. You feel a part of the music, because Hurt invites you in. It’s less a performance than an intimate conversation.

Hurt’s guitar style is rooted in traditions older than the Delta blues. Having learned songs from field hands and local musicians in his youth, his technique bridges the folk traditions of the South and the emerging blues idiom of the early 20th century. You’ll hear this synthesis in “Spike Driver Blues,” where the steady rhythm evokes the toil of a railway worker, and the melody winds around the tonic note with a bittersweet poignancy. His use of “double thumbing,” a technique where the thumb alternates bass notes with an additional rhythmic emphasis, adds another layer. Hurt’s ability to weave narrative and emotion into his playing is a mark of his humane artistry and the enduring appeal of his music.

Songs of Life and Loss

Hurt’s repertoire spans the breadth of human experience, from playful love songs to somber ballads. “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor” captures the yearning of a weary traveler, its melody lilting and tender. Hurt’s voice, soft yet assured, imbues the song with an ancient warmth. The steady pulse of his guitar is faithful like a clock, a quiet reminder that even passing comforts are precious.

“Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” showcases Hurt’s playful side. His nimble guitar work and winking delivery transform a lively tune into a celebration, one that feels both spontaneous and meticulously crafted. Hurt’s thumb provides a steady, driving bassline, while his fingers traipse across the treble strings, creating a rhythmically intricate and melodically buoyant arrangement. This interplay is further enhanced by Hurt’s unique ability to subtly vary his fingerpicking patterns, adding syncopation and energy without ever overwhelming the melody. His deft use of dynamics, alternating between moments of delicacy and exuberance, fulfills the song’s promise. The flutter kick — Hurt’s rhythmic flourish in his picking — infuses the song with a joyful energy.

Hurt’s rendition of “Louis Collins,” a murder ballad, reveals yet another dimension of his artistry. The interplay of his guitar lines with the narrative’s tragic weight transforms the brutal piece into a meditation on loss. Each note he sings is deliberate, every phrase carefully measured, like Hurt is our guide through life’s sorrows. In his hands, the story becomes more than a recounting; “Louis Collins” is all of us, a moment of communal mourning wrapped in song.

A Legacy of Quiet Brilliance

Hurt’s rediscovery in the 1960s was a miracle. Having been largely forgotten after his 1928 recordings for Okeh Records failed to gain commercial success, Hurt returned to a life of farming and playing music for his community. Yet when folklorist Tom Hoskins found him in Avalon, Hurt’s talent was undiminished. His performances at the Newport Folk Festival and subsequent recordings introduced a wider audience to a quieter, more introspective side of the blues.

Unlike the urbane, raw intensity of Robert Johnson or the driving rhythms of Son House, Hurt’s style offered a reflective, rural counterpoint. His music, with its soft-spoken charm, resonates deeply during a time of cultural upheaval, providing a bridge between the past and the present. Contemporary fingerstyle guitarists continue to draw inspiration from Hurt’s delicate interplay of rhythm and melody, his ability to create complexity through simplicity. His gentle demeanor and modesty endeared him to fans and fellow musicians alike, reinforcing the authenticity of his art.

The Eternal Flow of Hurt’s Music

Listening to Mississippi John Hurt is to step into a river of sound, its currents steady and its depths profound. Songs like “Avalon Blues” and “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor” remind us that you don’t need to be screaming and hollering the blues to be heard; it can whisper and still reach deep into your soul. Hurt’s legacy is not just in his technical brilliance but in his ability to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary. In his hands, a guitar has many voices, and each note the sound of the fingers of time.

Mississippi John Hurt’s music endures because it remains profoundly alive. Founded in long-gone styles and traditions, its beauty lies in its quiet conviction that a man can render the fleeting moments of a life with timeless tenderness and precision. These songs do not demand attention. They invite reflection, offering a counterpoint to a world that confuses noise with meaning. In Hurt’s hands, music is part of our long conversing with Paradise, the art and grace of a life well-lived.